5 of Munch’s artworks that talk about 5 different kinds of conflict

- Art Dealer Street

- Apr 21, 2023

- 4 min read

When we read the word “conflict,” the first example we think of is the one between Nations or entire populations, but conflicts can take on various different forms and occur on several fronts: identitarian, intimate, familiar, sexual, financial, as much as racial, religious, and political.

Conflicts can take place in the intimacy of our bedrooms, in dining rooms, in the workplace, on public transportation, and along the streets. Among neighborhoods, between colleagues, with parents, children, a partner or even oneself.

The world-renowned painter Edvard Munch has demonstrated the existence of this wide range of conflicts through his work by staging almost every kinds of fight in which a human being can find himself involved.

We have chosen five pieces that speak in a highly expressive way about five different conflicts: existential, physical, social, intimate, and sexual.

1. The Scream

Let’s start with one of the most iconic pieces by Munch, known all over the world thanks to its ability to convey the existential angst that pervaded much of contemporary society.

The painting depicts a man gripped by terror as he walks down the street, juxtaposed against a background of blackened fields and an orange sky; two small figures, anonymous and distant, increase the protagonist’s sense of loneliness and anguish.

The piece perfectly expresses the fear that each of us may feel during our lonely fight with existence.

2. Dead Mother and Child

We are in front of the heartbreaking painting of a frightened young child: the little girl is standing in front of her mother’s the bed, holding her ears to shut out the reality that she has died.

The painting is connected to the painter’s traumatic experiences from childhood and youth. Munch lost his mother to tuberculosis at the age of five, then went on to lose one of his sisters, Sophie, nine years later who suffered from the same life-threatening disease; moreover, his sister Laura became depressed.

The devastated figure of the child in her silent horror reaches out to the viewer, talking about the fight that, at some point in our lives, we will have to face not only with our own physical health, but also that of those close to us.

3. Evening on Karl Johan Street

The painting depicts the evening walk for citizens of Christiania (today: Oslo) on Karl Johan Avenue, the pulsating heart of city life.

Instead of sophisticated bourgeois men, we see a procession of masks with deformed yellowish faces and vacous eyes. Rather than human beings, the members of this funeral procession make one think of zombies, the spiritually empty creatures that seem to move forward ineluctably, giving rise to a feeling of suffocation. Munch, in particular, emphasizes this sense of oppression by cutting all the figures at chest height, so they overwhelm viewers as they advance toward them.

In this painting, Munch perfectly describes the conflict one could have with the society in which he/she belongs but does not share the rituals and conventions, therefore feeling alienated.

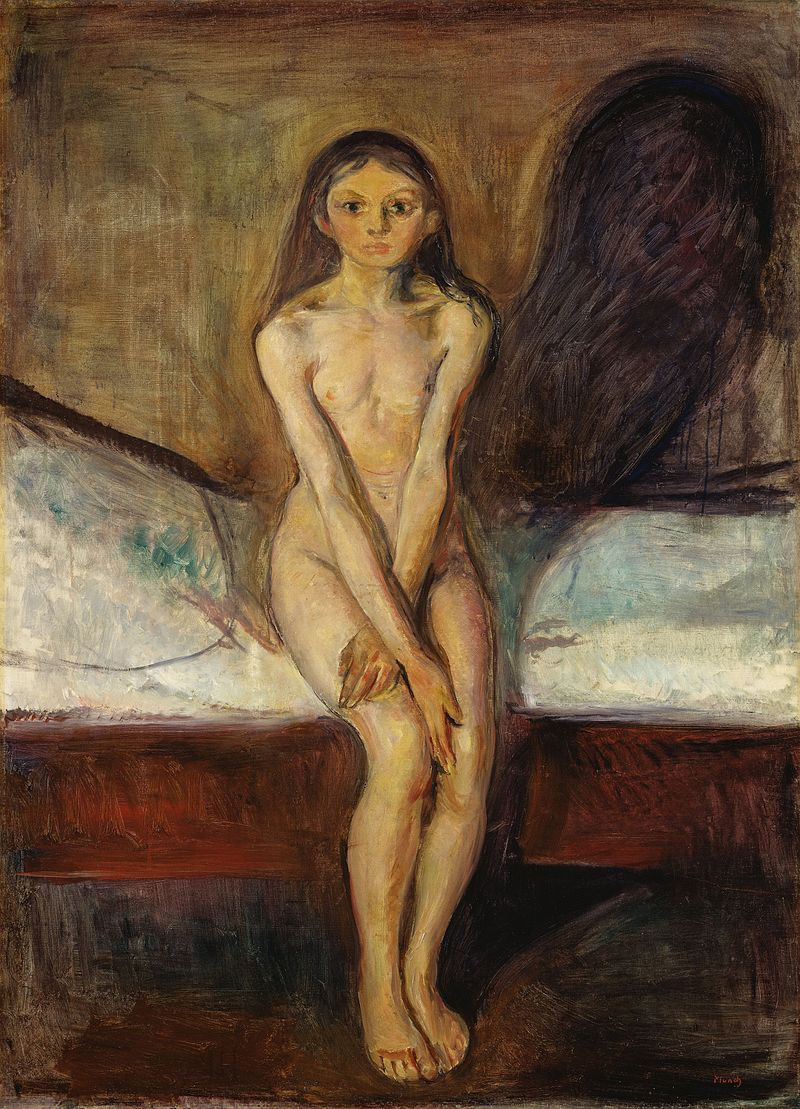

4. Puberty

A young girl stands in a bare, desolate environment that almost looks like a prison cell. Sitting, naked and alone on the edge of her bed with her legs clasped together, she holds her arms crossed over her pubis in a shy, virginal gesture. She is visibly troubled by her own thoughts: her gaze is fixed and frightened, her eyes are wide open, her mouth is tight.

Thanks to the light coming from the left, the virginal body casts a threatening shadow against the wall that seems to be a dark and uncanny double of her personality: it is, in short, the symbolic projection of her inner state.

This work perfectly expresses the conflict each of us feels with our bodies during the problematic transition period known as puberty. The young woman, alone in the privacy of her room, must fight with the discomfort she feels with her changing body as she struggles to recognize herself.

5. Vampire (Love and Pain)

As for The Scream, this work has also become an iconic one; however, few are aware that the piece’s original title was not Vampire but Love and Pain: the title by which we all know it was given in retrospect by the critic Stanisław Przybyszewsk.

This fact is indicative of Munch's troubled and ambivalent attitude toward couple relationships, which he expresses through his work.

The painting shows a woman with long red hair kissing a man on the neck as the couple hug each other. Munch himself said that he was showing nothing but "just a woman kissing a man on the neck."

However, from the viewer’s perspective, the man appears locked in the arms of a vampire and the kiss turns into a bite. What in the artist's mind was intended to be a tender and caring gesture resembling a consoling embrace, actually depicts a creepy scene. The man, squeezed in the dangerous embrace, is overwhelmed by the power of the vampire woman, whose waterfall of red hair envelops the entire composition and drips onto his head like drops of vivid blood.

This ambivalence resembles the conflicts that mark the daily life of couples or of anyone involved in an intimate relationship.

The selected works are almost all part of the series The Frieze of Life, which is a narration not only of Munch’s personal journey exploring his internalized conflicts as an individual, but also functions as a mirror of the growing anxiety and common struggles of modern times and of contemporary society.

First exhibited as a group of six paintings in 1893, the collection grew to a total of 22 works by the time it was first shown under the The Frieze of Life title in 1892. Permeated with symbolism, these works explore the universal human experiences of love, illness, loss, and despair by highlighting the permanence of conflict in all phases of our lives.

Comments