Inside the Studio: Sori Choi

- Art Dealer Street

- Dec 9, 2025

- 9 min read

Some artists chase silence. Others turn sound into something we can see.

For Sori Choi — once a powerhouse drummer in Korea’s iconic heavy-metal scene and later a celebrated percussion soloist — sound has always been far more than noise. It is vibration, collision, memory, and emotion. When hearing loss threatened to take that world away, he didn’t step back. He struck harder — discovering a new artistic language where rhythm becomes mark-making, and energy leaves traces that shimmer, dent, and breathe.

Today, Sori lives and works between performance and nature. In Cheonghak-dong, deep in Jirisan Mountain, he places metal plates into water, wind, soil, and stones, letting nature compose the first notes. Once they return to his hands, he engraves, scratches, and polishes them like instruments — creating surfaces that pulse with Visible Sound.

Read on to learn more in an exclusive interview with Sori Choi :

You began as a renowned percussionist and drummer before expanding your practice into visual art. Can you share the moment when you first felt the need to “make sound visible” and turn your musical journey into paintings and installations?

In my youth, I performed as the drummer of Korea’s leading heavy metal band, communicating with the world through intense rhythm and energy. Later, I transitioned into a percussion soloist, exploring the essence of music through my own original techniques. But one day, I was diagnosed with severe noise-induced hearing loss and faced the devastating possibility that I might no longer be able to hear sound. In shock and despair, I returned to the practice room, throwing down my instruments and sticks in anger. Days later, when I revisited the space, the walls still bore the violent traces of that moment.

It was then that I realized: the very acts of throwing and striking could themselves become another language, one that visualizes emotion. In the fear of losing sound, I discovered a new hope. From that point on, I began inscribing the traces of my performance onto paper and metal plates, transforming invisible waves into art that could be seen. It was another hope born from despair. Music was no longer confined to sound alone, but expanded into light and form, becoming my new journey.

In your work you say that “every object and energy has its own sound,” and you treat dents, scratches, and holes as traces of that sound. How do you choose the materials you work with—aluminum, copper, brass, paper, canvas—and what different “voices” do you hear in each of them?

The choice of material is not a mere technical decision for making art, but a process of finding a medium through which my body, rhythm, and traces can endure over time. I consider the inherent properties of each material, the changes revealed through time, and the unique resonance embedded within them. A material is not simply a surface—it is an instrument, a voice, and when combined with my gestures, it creates new resonance.

Aluminum carries a clear, cold resonance. Its transparent metallic vibration produces a sharp yet crystalline sound, leaving waves of light across the surface. Copper holds a warm, deep resonance. Its surface oxidizes and changes color over time, and that transformation itself becomes another rhythm and resonance. Brass embodies weight and strength. Marks of impact and abrasion are inscribed with intensity, and its profound resonance supports the entire structure of the work.

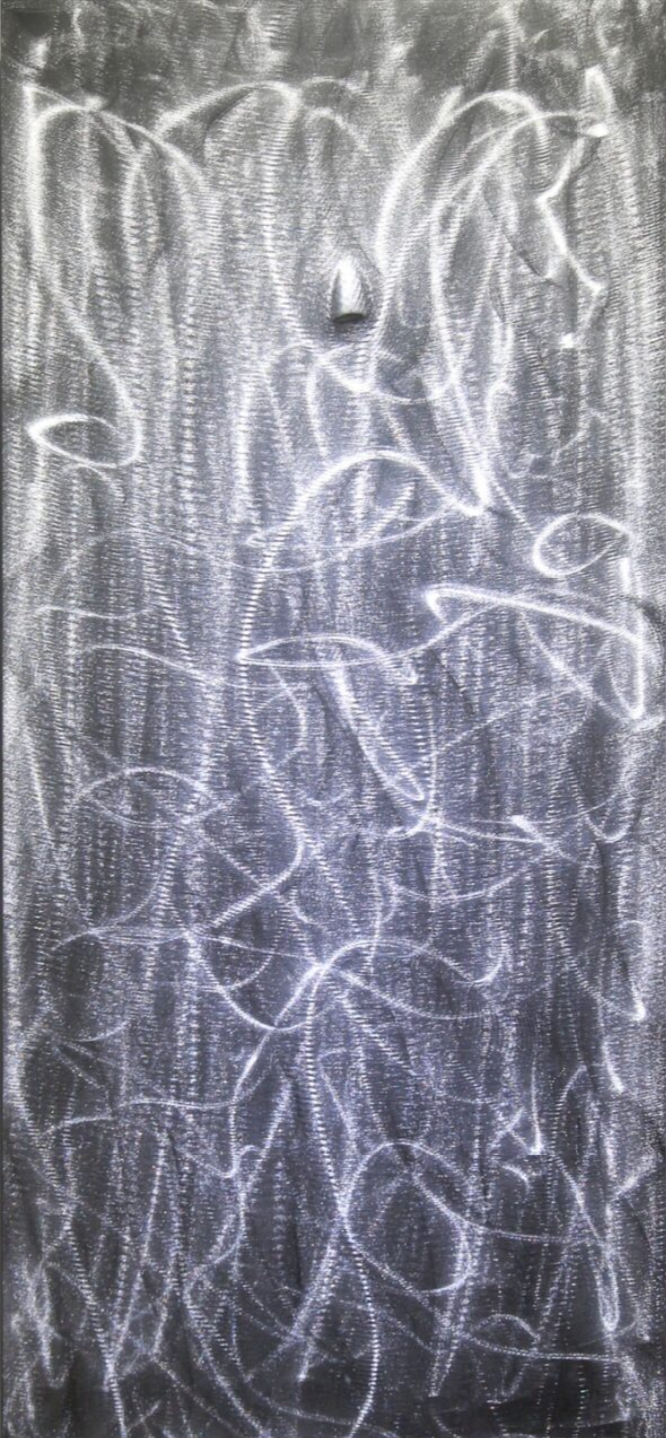

Paper and canvas breathe in a different dimension than metal. Paper is delicate and sensitive, responding instantly to even the smallest trace, producing a light resonance like breath. Canvas contains a more flexible, sustained rhythm, offering space for patterns to expand and spread across the surface.

Ultimately, each material has its own voice, and I work by listening and responding to it. Dents, scratches, and holes are not mere marks but records of the sound spoken by the material. When my gestures and the voice of the material converge, music and art are no longer separate—they are completed as one world. It becomes a synesthetic field where sight and sound, matter and sensation intersect, and the viewer resonates inwardly with the unique voice of the material.

Many of your works are created in Cheonghak-dong in Jiri Mountain, where you let metal plates rest in the forest, water, earth and stones before working on them. What does a working day in this environment look like for you, and how does living so closely with nature change the way you create?

A day in Cheonghak-dong, deep in Jirisan, is not simply time for work but a ritual of coexistence with nature. In the morning, I greet the forest’s light and wind, receiving the day’s energy into my body. Placing metal plates by the water or burying them in the soil is not just a technical process—it is a rite that allows nature to inscribe its marks upon the work first. I watch and wait for the rhythm of transformation that nature creates.

This environment constantly reminds me that humans are part of nature. The plates oxidize under sunlight, corrode in water, and acquire new textures through wind and soil. At each moment of change, I intervene to add traces, then return them to nature, repeating the cycle. This is not unilateral creation but a co-creation between nature and human.

Living so closely with nature has fundamentally changed my creative process. Urban time is linear and efficiency-driven, but mountain time is cyclical and demands patience. A work is not completed quickly; it slowly takes shape with the flow of seasons. This slower temporality gives the work depth, so that when viewers encounter it, they experience not just an image but the condensed traces of years of breathing and waiting.

In the end, as I live within nature, I become nature, and nature permeates me. This is not a mere metaphor but a mode of artistic practice. True collaboration begins by dwelling together long enough to become one. The work, as a result, is a record of resonance—human and nature reflecting each other’s existence.

Series such as Fire, Wind, Water, Earth, Life explore the four elements and a “fifth element” of life and emotional resonance. How do these elements guide your compositions, and what kind of feelings or states of mind do you hope viewers experience when they stand in front of these works?

The “Five Elements Series” is not simply about using natural elements as motifs, but about weaving together the rhythm of my body and the breath of the seasons. Fire symbolizes inner energy and creative explosion; Wind embodies invisible currents and freedom; Water conveys fluidity and healing power; Earth represents the fundamental ground and roots of life; and Life, the fifth element, connects them all, evoking emotional and existential resonance.

I feel that nature draws first within the cycle of the 24 seasonal divisions. The light, temperature, humidity, and texture of the wind already leave traces on the surface. My role is to add technique and emotion, completing the melody that nature has begun. Thus, the work is not solely mine, but a trace of a performance shared with nature.

When viewers stand before the work, I hope they experience more than an image. I want them to feel the intersection of natural order and human interiority: passion in the heat of fire, freedom in the flow of wind, healing in the movement of water, grounding in the weight of earth, and self-awareness in the resonance of life.

This experience cannot be reduced to a single emotion. Rather, viewers encounter a multilayered experience of breathing together with nature. For a moment, they step outside the time of daily life and entrust body and mind to the order of the great natural world. The work approaches them not as something to be seen, but as something to be lived.

Your process of striking, grinding and polishing the surface reads almost like a performance on the drum. When you work on a piece, do you feel more like a musician or a painter, and how does rhythm shape the final image on the metal or canvas?

My work exists in a constant flow between music and art. Striking, grinding, and polishing the surface are not mere processes of making, but bodily memories that recall rhythms engraved through years of performance. I handle metal and canvas as if playing instruments; sometimes they resonate like the skin of a drum, sometimes they respond like the vibration of strings.

Thus, I do not define myself solely as either musician or painter. I stand at the intersection of both identities. Music flows through time and vanishes, while painting fixes its traces in space. The surfaces I strike and scratch are devices that capture the traces of that flow. Viewers, in turn, sense not only visual images but the rhythm embedded within them.

Rhythm is not a background element but the very structure and resonance of the final image. Repeated impacts create pulses across the surface; abraded textures spread like waves; polishing produces vibrations of light. The work can be read as a score and heard as a performance. When seeing becomes hearing and hearing becomes seeing, music and art merge into a single language.

What matters to me is not “what was drawn” but “how it resonated.” The marks left on metal and canvas are not mere images but records of resonance born from the intersection of body and rhythm. When that resonance reverberates within the viewer, the work is truly complete.

In several texts you speak about resonance, trance, and even “hearing” waves of sound in the paintings—almost like synesthesia. How do audiences usually react to your works in person?

Viewers’ responses to my work fall into two broad groups: those who have experienced my performance directly, and those who have not.

Those who have seen my performance perceive more than visual images in the work. They describe sensing inner vibrations resonating across the surface, as if hearing waves of sound. This is not literal sound but sensorial resonance created by visual rhythm and the texture of matter. In that moment, painting expands beyond seeing into hearing and feeling—a synesthetic transfer where sight evokes sound and touch.

By contrast, viewers unfamiliar with my performance often struggle, asking, “What sound is this? Is there really sound here?” They approach the work as a reproduction of sound, but my intention is not to mimic sound directly. Rather, it is to render the traces and vibrations left by waves in visual form. Those who have witnessed the performance connect immediately, while others find it harder to grasp the link.

Ultimately, my work explores the gap between seeing and hearing. The surface is not merely color and texture, but a record of waves, which stir resonance within the viewer. Some call it sound, others vibration or energy. What matters is not identifying a specific sound, but experiencing the crossing of senses that generates new perception.

Works like If you were the wind and the Collaboration of Light and Sound installations invite viewers to move around them and experience light, reflection and space. What role does the surrounding architecture and the movement of people play in completing these pieces?

My works do not exist in isolation; they are completed through the architectural space that surrounds them and the movement of viewers within it. If you were the wind unfolds in the vast space of Starfield Goyang, where light and reflections constantly shift. As viewers walk around the cylindrical form, visual waves change like the wind. This transformation becomes another performance, created jointly by the architectural environment and human flow.

The same is true of Collaboration of Light and Sound. Light leaking through the gaps in metal plates is not fixed; it reveals different expressions depending on the viewer’s gaze and movement. In each moment, light, sound, and space generate new resonance through the mediation of the viewer’s body and senses.

Thus, architectural space becomes the stage, and human movement becomes another performance upon it. The work is not a static object but a living presence, continually completed anew through the breathing of viewers and space together.

Looking ahead, are there particular sounds, places or human experiences that you still feel compelled to capture in your “visible sound” works? Is there a dream project or collaboration you would like to realize in the future?

“Visible Sound” is not merely an artistic experiment, but a journey of sensing and recording the messages exchanged between the world and human existence. In every object, energy, place, and human experience I encounter, I hear a unique resonance. It is an invisible wave, a voice that leaves traces of life.

Looking ahead, I wish to capture even more fundamental sounds. For instance, spending an entire day with children in nature, immersed in pure play and collaboration, would reveal the sounds and laughter that arise from humanity in its most essential state. These are rhythms uncalculated, waves of pure life, showing the most primal power of art.

Working with those approaching death also holds profound meaning for me. The final moments of life are a process of laying everything down and emptying oneself, and the resonance that emerges at that threshold is the deepest sound that bridges life and death. By recording that moment through art, I hope to reveal the essential vibration of human existence.

Ultimately, my dream is not confined to a specific place or person. I see the entire world as one vast score, within which humanity and nature, life and death, joy and sorrow intersect to create multilayered rhythms. One day, if possible, I hope to collaborate with diverse artists to realize a total project where music, dance, and visual art converge. That would be the moment when “Visible Sound” transcends a single genre and expands into the universal language of art.

Sori Choi’s practice begins where others might stop — in the moment when sound slips away. Every strike he makes is a memory of impact. Every polished wave catches light like a note suspended in air. His works are not images; they are records of resonance — a meeting point of body, nature, vibration, and time.

He invites us to listen with our eyes. To feel with our senses. To recognise that nothing in this world is silent.

Through metal, rhythm, patience, and breath, Sori shows us that sound never disappears —it simply finds a new way to be heard.

You can learn more about Sori Choi and his work via these links:

Comments