What doesn’t kill us makes us happy?

- Alessandro Berni

- Mar 30, 2021

- 7 min read

More than half a century ago when El Museo opened its doors in East Harlem, Latin American art community didn’t do very well. I mean, Latino artists were just excluded from the national-level exhibition practices along with the other socially vulnerable groups, such as Black people, members of LGBT society, and yes, even women at that time. While calling on the sense of justice of the mainstream museums’ directors was hardly feasible, artist and educator Raphael Montañez Ortiz made his way establishing an art institution primarily devoted to Puerto Rican culture. The idea to celebrate and promote Puerto Rican artists as well as educate the local audience has developed into a solid initiative focused on all kinds of Caribbean and Latin American arts. Based in the heart of “El Barrio”, the eponymous museum has come up with some life-affirming Latino exhibitions ever since.

ESTAMOS BIEN

ESTAMOS BIEN1: LA TRIENAL 20/21, the exhibition you can currently see within El Museo and partly on their website, comes as a logical continuation of the institution's previous projects, yet it’s unique in several aspects. Since 1999 El Museo del Barrio was running The (S) Files Bienal, which seeing a handful editions and months of the museum’s renovation, has been eventually reconceived in the format of a trienal. Remarkably, the Bienal’s editions never shared the same curators or artists invited, helping the viewer to discover new promising names each time.

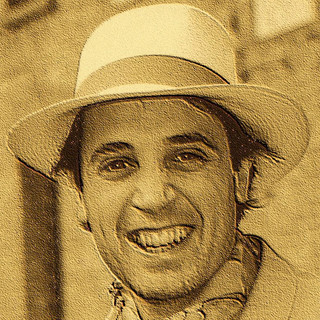

Puerto Rican artist and singer of the Estamos Bien lyrics (2018) Bad Bunny (2). Photo_ STILLZ

Originally The (S) Files Project (S stands for selective here) was launched as a platform for showcasing works by talented Latino artists. I find the word “files” in the exhibition title very fitting, because, in some sense, it was a real archive, handpicked and broadly representative of the topic, which is, generally speaking, an arduous path of Latin American creatives, both in life and arts. Although a couple of The (S) Files editions were issue-specific like the one focused on the street aesthetics (2011—2012) and Here is Where We Jump (2013—2014), none of the El Museo Bienals really followed any narrow area of research. Just the opposite: the assigned topics endowed the shows with a beautiful name… and even more extended their concepts to celebrate diversity and resilience of the Latin American artists.

This also seems true about ESTAMOS BIEN Trienal. The name of the project refers to the title of the work by Candida Alvarez, one of the participants and the only artist in the show who has previously worked with El Museo. Besides, ESTAMOS BIEN makes one think of the self-titled song by the Puerto Rican singer Bad Bunny, a vigorous and a bit harrowing track at once. The exhibition co-curator Susanna V. Temkin explains that while the show has taken on new connotations because of the 2020 overwhelming events like the global pandemic and the Black Lives Matter precedents, now it “reflects both sarcasm and serves as a provocation”, which one can hear from the title.

Lizania Cruz, Obituaries of the American Dream (2020–21). Courtesy the artist

Indeed, the Trienal couldn’t but soak up the bitter taste of reality, yet ESTAMOS BIEN had been in formation for some time by the previous year, so was its concept… The curators decided to expand the exhibition for a year, prefacing the major onsite display with a couple of online projects (among the featured artists are Lizania Cruz, Michael Menchaca, Poncilí Creacion, Collective Magpie, and xime izquierdo uga) launched back in summer 2020. It feels like the “starting low, aiming high” approach of the Latin American art community (by no means to be confused with the idea of the American Dream) was initially implied and just exaggerated by the incidents that followed.

So, does that mean that all artists at ESTAMOS BIEN intended to talk back to the imaginary question, which sounds just as banal as the weather talks do? Opinions differed, among the 42 participants of the show, both individuals and collectives (which is, by the way, nearly twice as less than in 2011), one-half subtly addressed the global issues like social exclusion, poverty, prejudice, and oppression from the position of the first-hand experience, while others expressed their outrage with how things work today right in the face of the viewer. It’s interesting that the degree of credibility in works didn’t necessarily correlate with the chosen form of an artistic statement, either based on one’s own experience or witnessed from without… So as to back up my remark, I’ll provide a few insights from the display here.

Joey Terrill, Black Jack 8 (2008). Courtesy of the artist

Obituaries of the American Dream (2020–21) by the Dominican-born artist Lizania Cruz served as a prime example of a participatory project, where the invited attendees uttered the artist’s distrust with the overrated national concept without being forced to do it in any way. The participants of various backgrounds and social statutes shared their testimonies of when and how the American Dream died for them, with the resulting content being issued in a series of print newspapers.

Another example: the art duo Pablo and Efrain Del Hierro a.k.a. Poncilí Creación collective successfully implemented their practice of making foam rubber sculptures into another spectacle, a durational procession against the repressive reality inhabiting the neighborhoods of San Juan. Titled as Somxs Podemx (2020), the performance contributed to Poncilí Creación’s devotion to building links between communities and collecting resilience among the people impacted. Both projects can be viewed online.

Poncilí Creación, Somxs Podemx (2020). Video installation (1). Courtesy of the collective

Meanwhile, some of the works presented at ESTAMOS BIEN were less successful in conveying the message, either failing to articulate it, or vice versa, generalizing it. Thus, Sé Que Fue Así Porque Estuve Allí by the South American non-binary multimedia artist xime izquierdo ugaz rather implied than showed the intention of the author, despite being fully in line with the trienal’s concept (we’ll get to that later). Portraits of xime’s chosen QTPOC family looked engaging as well as the vague, ironic remarks written by her sworn siblings did, yet the links and the back-story of that kinship remained unclear, which inevitably cooled down one’s interest towards the work.

On the contrary, one can hardly think of a clearer artistic statement than in the case with a 2018 video by the collective Torn Apart/Separados. The high-tech data visualizations showcased the notorious dynamics of family separations in the US (and the source of the problems), which seemed more than convincing, however, behind the impeccable facade of the work the artists’ personal attitudes and involvement in the issue were silent.

Entrance of El Museo Del Barrio, Fifth Avenue, New York, NY. Photo_ El Museo Del Barrio

If it comes to decide on the artworks that got straight to the point of the Trienal, I would opt for the Black Jack 8 painting by the Los Angeles-based artist Joey Terrill (one of the oldest participants of the project, by the way). The 55-year-old native Angeleno, regular of the local queer art circles, Terrill, for much of his career, has been focusing on public response to the HIV positive status of queer people, especially from those who make money treating the virus, i.e. pharma companies. Lavishly painting the mouth-watering achievements of the American FMCG market such as enormous exotic fruits, glittering Coke and 7up bottles, glazed pastries, the artist almost casually put some anti-HIV drugs on the table, alluding to the absurdity of consumer culture (but, as a person with a 40-year experience living with HIV, Terril accepts he has nothing against using the tablets). Black Jack 8 is also interesting because it vividly demonstrates the painter’s unique manner grounded in conceptual art and pop art aesthetics and topped by Chicano creative energy Joey Terril was greatly influenced by in his youth.

So after all, what is it that makes ESTAMOS BIEN: LA TRIENAL 20/21 so different from the past (S) Files editions, so appealing? Apart from the outstanding title, of course. The thing is that the concept of the show centers on the definition of Latinx [luh-TEE-neks], which, in case you didn’t now, is meant to describe people of Latin American origin in the US in a gender-neutral way.

The latter constitutes a very important part of the concept, while many Latino Americans have got sick and tired of being addressed by the binary terms that usually hurt the feelings of those who see themselves beyond the bounds of the hierarchical system.

Candida Alvarez, Estoy bien (2017). Courtesy of the artist

Although not all artists at ESTAMOS BIEN demonstrated their involvement in the new conception (at least, some of them did, including xime izquierdo ugaz and Joey Terrill), the ice has been finally broken. ESTAMOS BIEN: LA TRIENAL 20/21 is the second museum major exhibition after the Whitney’s 2018 Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay project to feature and celebrate Latinx artists. And as for the title of the Trienal, it could have also been (mixing the names of the artworks recently discussed) ESTAMOS BIEN POR QUE SOMOS [LO QUE SOMOS] Y PODEMOS2. Thus, El Museo del Barrio has turned a new chapter in the history of resilience of Latin American art. And let Bad Bunny perform his bold lyrics in honor of that.

P.S.ESTAMOS BIEN1: LA TRIENAL 20/21 is on view to the public in Las Galerías at El Museo del Barrio from March 13 to September 26, 2020. The show is curated by the Museum’s Chief Curator Rodrigo Moura, Curator Susanna V. Temkin, and artist Elia Alba as Guest Curator. The trienal features works by the artists Francis Almendárez, Candida Alvarez, Eddie R. Aparicio, Fontaine Capel, Carolina Caycedo, Juan William Chávez, Yanira Collado, Collective Magpie, Lizania Cruz, Amaryllis DeJesus Moleski, Dominique Duroseau, Justin Favela, Luis Flores, ektor garcia, María Gaspar, Victoria Gitman, José Antonio Gómez, Manuela González, Lucia Hierro, xime izquierdo ugaz, Esteban Jefferson, Roberto Lugo, Maria José, Carlos Martiel, Patrick Martinez, Yvette Mayorga,

Groana Melendez, Michael Menchaca, The Museum of Pocket Art, Dionis Ortiz, Poncili Creación, Simonette Quamina, Vick Quezada,

Sandy Rodriguez, Yelaine Rodriguez, Nyugen E. Smith, Edra Soto, Joey Terrill, Torn Apart/Separados, Ada Trillo, Vincent Valdez, and Raelis Vasquez.

More detailed information about the project can be found on the museum website.

1 Estamos bien — Spanish for “We are fine”

2 May be translated as “We are fine, because we are who we are and we can do that”

Comments